| Katja

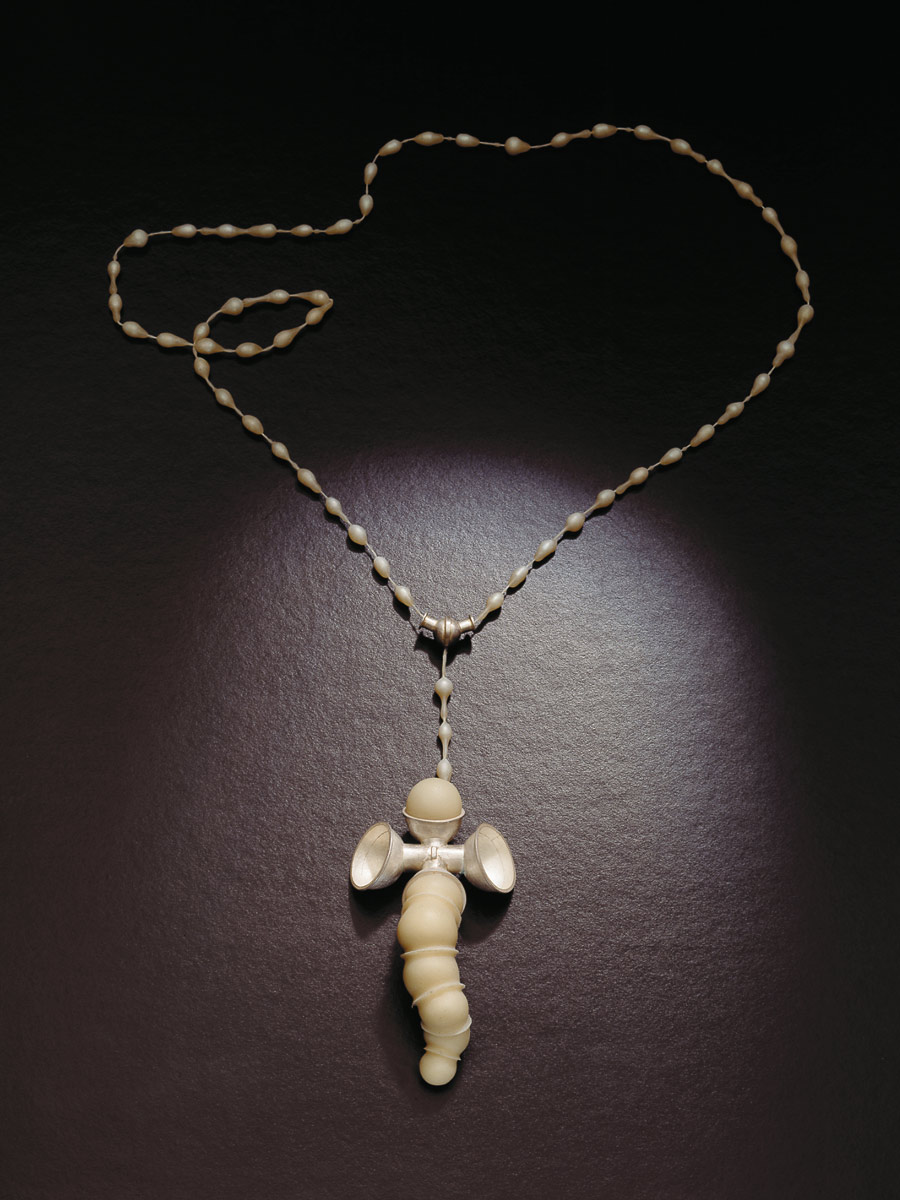

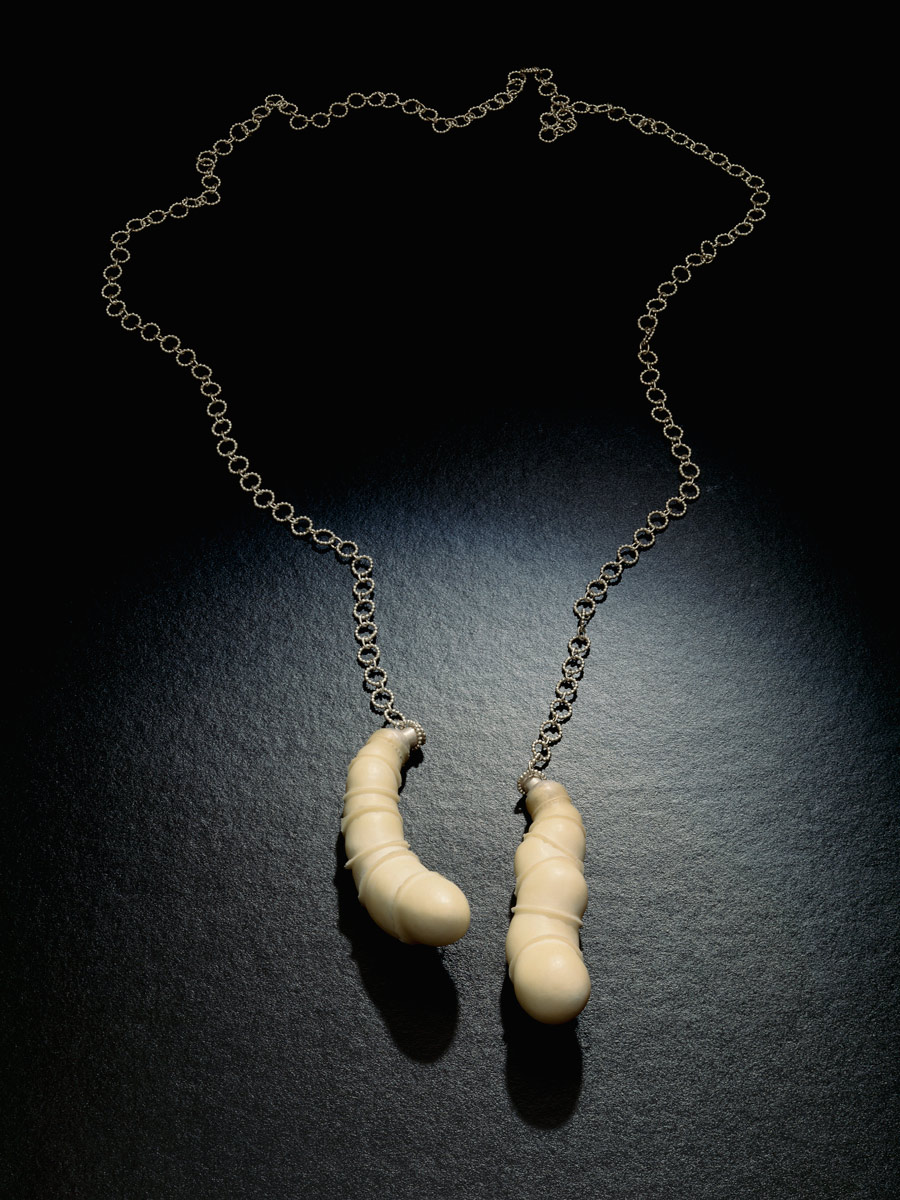

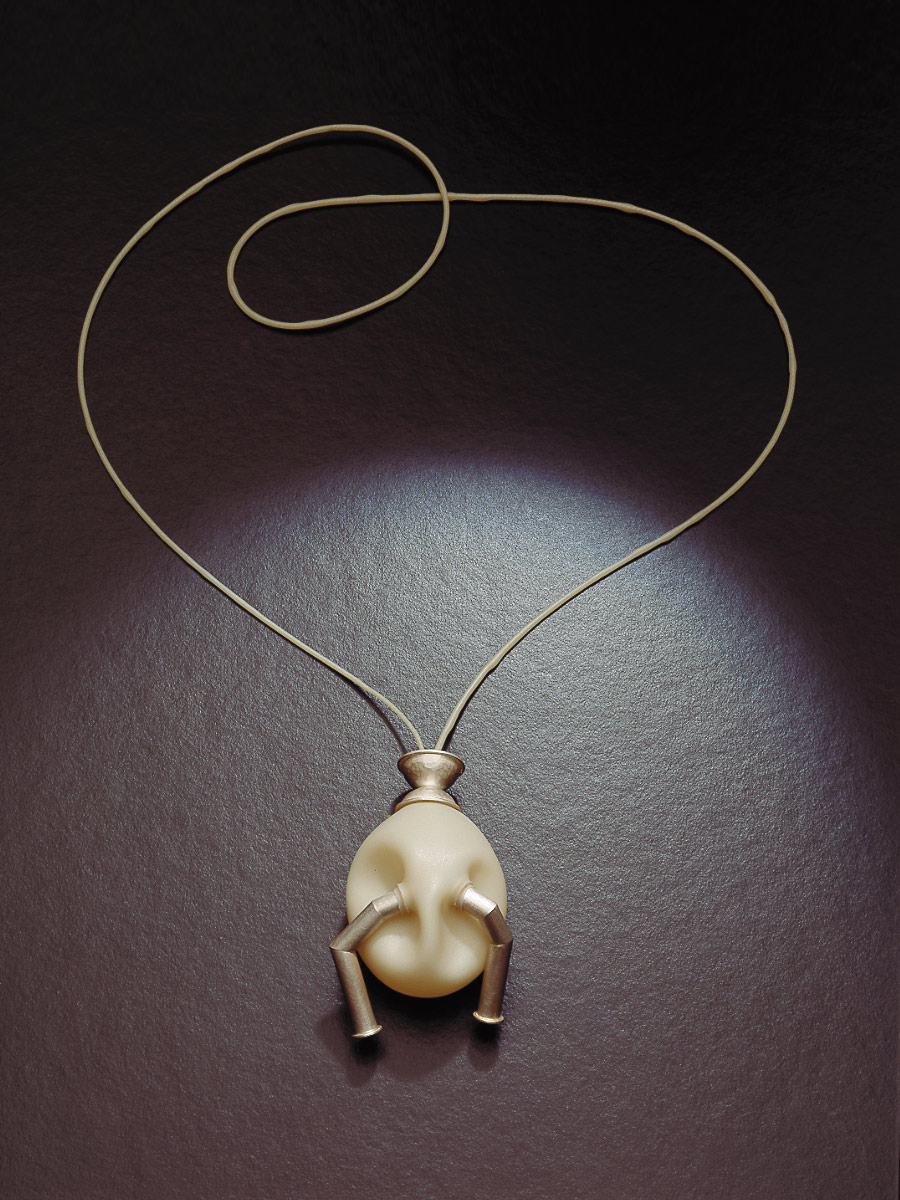

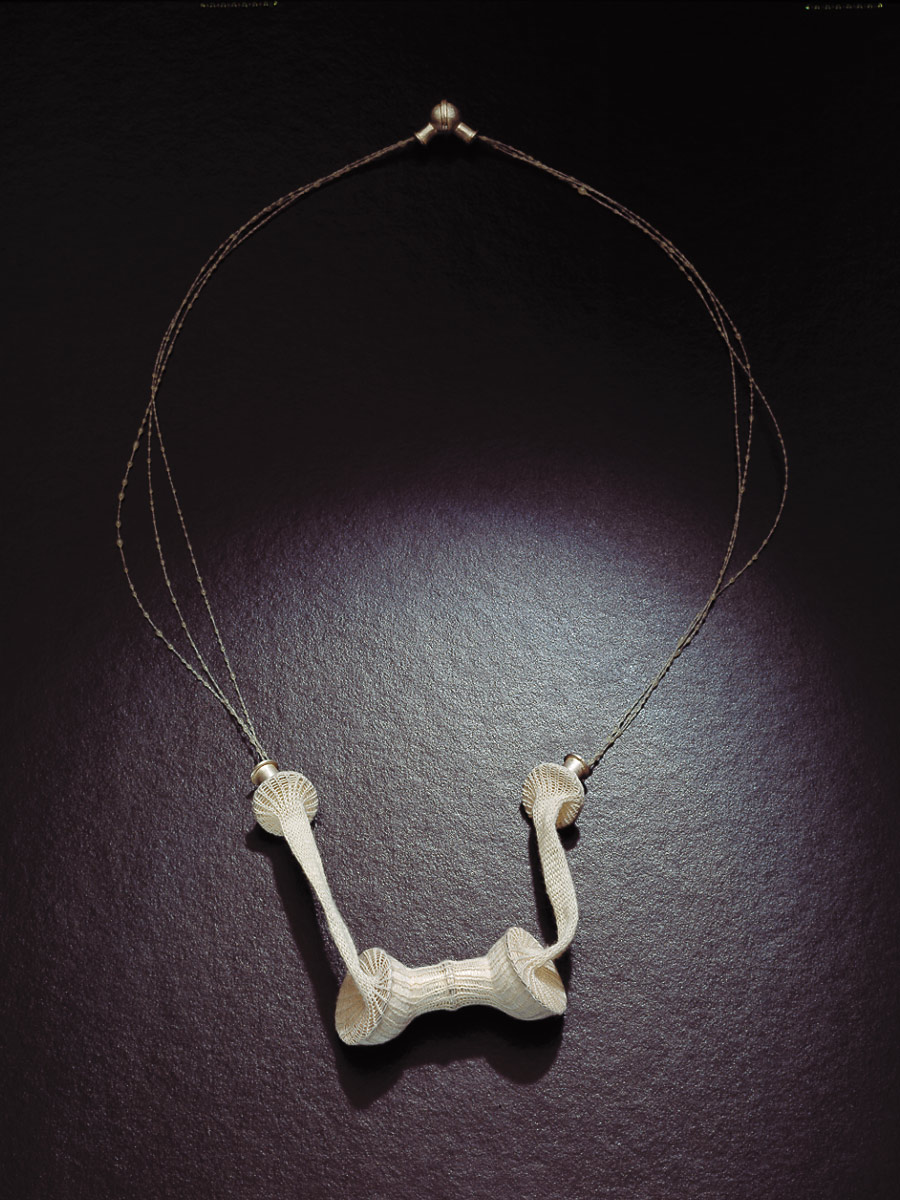

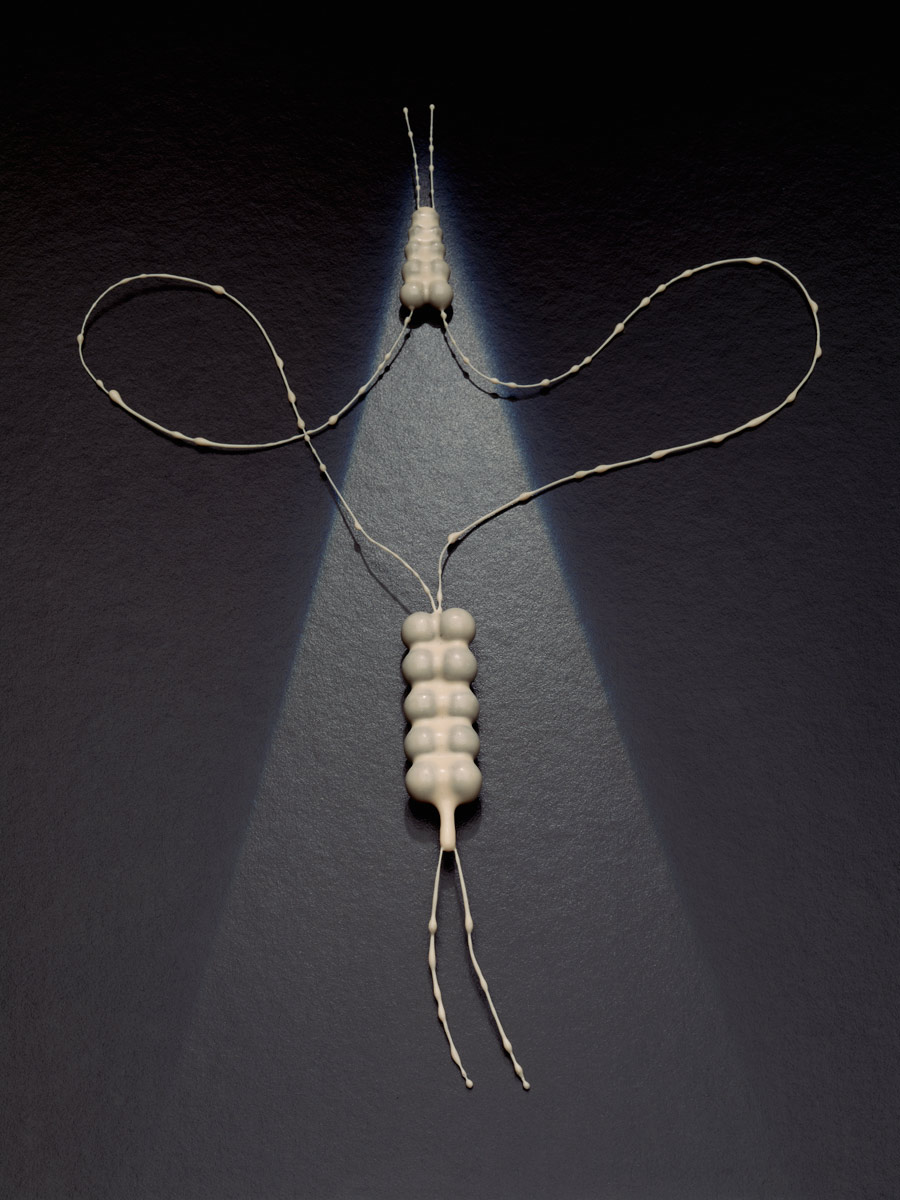

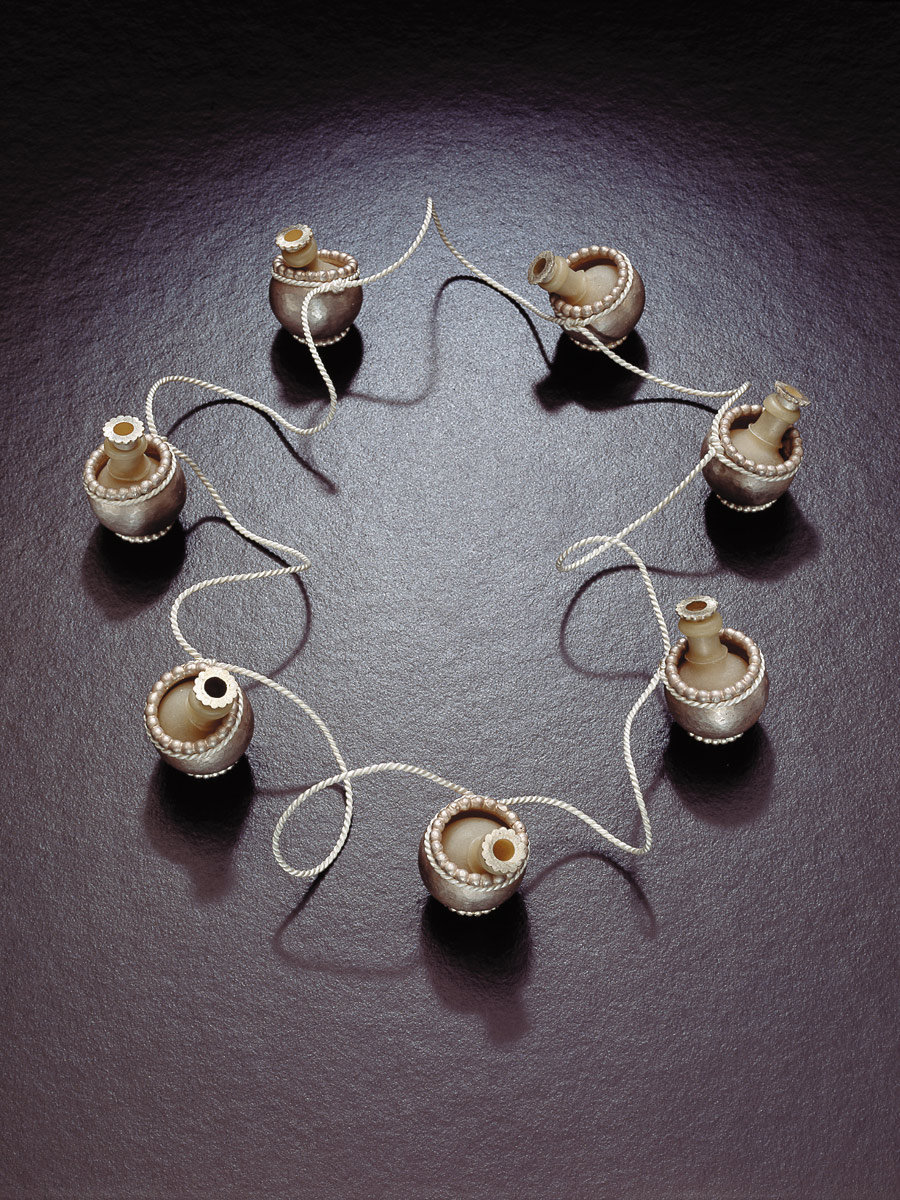

Prins' emotional machines "Machines are us" - Katja Prins' works of 2004 and 2005 - are the identification of the artist's intimate feelings with technological processes which overcome the controversial dialectics of her previous works, in her search for the relationship between nature and mechanics. Since the early 20th century, with the revolutionary culture of historical avant-gardes, machines had violently entered the visual language, even theoretically, as in Futurism, which celebrated their progressive values. The same can be said of Fernand Léger's Cubism, which humanised machines. The Surrealist movement also used machines identifying mysterious psychic processes in their automatisms. In the 1920s and 1930s, the close connections between sculptural and pictorial experimentations with artistic jewellery were confirmed through works by great artists, genial precursors of contemporary goldsmith's art. Machines were triumphantly included in the designs of rings and necklaces by Jean Desprès. He was an incomparable researcher of possible technological applications in jewellery, keeping the indispensable "physiological" components in adhesion to the body. Besides Desprès, other important jewellery artists of the 20th century, mostly French, such as Raymond Templier, Gérard Sandoz, Georges and Jean Fouquet applied mechanical solutions used by famous Cubist designers, like André Léveillé, Adolphe Mouron, and Jean Lambert Rucki. Machines became idols, emblems of constructive and destructive powers, and symbols of freedom or further human constraint, as expressed in well-known movies of the time (e.g. "Metropolis" by Fritz Lang, or "Modern Times" by Charlie Chaplin). Instead of the great 20th century experimentations, Prins considers the creativity of European masters who, in the second half of the same century, provided new and original meanings of mechanical representations. Dutch culture of the 1960s and 1970s, in its Minimalist practice, was the first to carry out technological experiments: Emmy van Leersum's steel necklaces - large winding collars which, arranged around the neck, include the chest and even the clothes - marked a trend, which later developed with other important contributions from - for example - Gijs Bakker, Françoise van den Bosch, and Paul Derrez. In that period, other European artists invented shapes which were absolute technological entities. Peter Skubic transformed structures into continuously changing expanded areas, in which the tensions between metal lines created spatial values. Fritz Maiehofer's works came into being in a kaleidoscopic world of mechanical structures, in which matching colours are frantically emphasised to turn into an impersonal universe of Pop-Art iconography; Claus Bury combined industrial diagrams with ecstatic and esoteric figurations projected into a metaphysical world. This production, which had many followers, conceived technology as the rigorous application of logical rules expressed by the abstract-geometric culture. On the contrary, Prins' work develops in a post-modern cultural context, which characterizes - with different manifestations - the youngest generation of artists in Holland. Imagination is free, often memorialist, impatient to recover past shapes, modes, and styles, imbued with profound naturalistic passion. Prins marks the transition from organic to mechanical idolatry. The artist shows how she both strives to analyse nature and needs to represent it in a rigid way. Her synthesis of two opposed entities is applied in a transformist vision, as compared with the conception of masters who came to mechanicism through the persistent conjugation of the geometrical vocabulary. Since her early works of 1999 - the "Rubber Collection" - Prins' works show a materic tension as she uses white polyurethane to design shapes with a constantly metamorphising ambiguous, zoomorphic, floral naturalism, which does not exclude references to human organic details. Internal emptiness creates pulsions that blow plastic, forming spheres of various sizes, at times pedunculated, sometimes projected into long, tormented appendixes which suggest the energetic effort of possible sexual erections. The erotic reference in animals or flowers is shrouded with mystery and chasteness, almost a censorship, as polyurethane "cruets", inserted in round, partially coated silver containers - sometimes partially hidden by crochet meshes - emerge alive like fertilising organs. In the later works, the "Inventarium" series of 2002, the emotional and vital charge seems diming in the return of complicate relations between medical instruments and the body, whose suggestions remain in modulated forms of white porcelain. In their rounded surfaces they show an innumerable series of black drawings, inscriptions, measurements, numerations, and layouts: they look like notes for possible archives, aimed at documenting the use of appliances. However, they lose their function and rather appear as archaeological findings. Prins' complex "Machines are us" is an essential part of her work. All lyrical abandonment, memory, and emotion are consolidated in the most rigorous and plastic monumentality: an epic of nautical and aviation instruments, where aerodynamic tension is constantly opposed to minimal structural elements, technical details of water or power supply systems transformed into graphic markings on the smooth parts of aircraft bodies or hulls. Prins represents an entire universe articulated between grey polystyrene and silver, where shapes are rigorously positioned in volumetric orders marked by essential linearity. However, her naturalist tendency violently shakes these almost static images: in 2005 and 2006 Prins' works "Flowerpiece" show how the artist enlivens wings and propellers by transforming them into corollas of flowers in the centre of which there is an indented pulleys, or decomposing grey fuselages into multiple corymb inflorescences. The "Continuum" series of 2007 shows a composition reduction once again dominated by white colour, lightening the outlines: so much lightness originates from previous long experimentation with glass used by the artist to create net transparencies of containers, cups, amphorae, alembics with unpredictable solutions in the movements of spouts and bottle necks. The images in this last series seem being outlined in an empty space determined, circumscribed, and highlighted by the clearness of shapes: ellipses, circles, segments, through their surfaces - from whiteness created by the covering layer of kaolin on silver - find balanced correspondences with red colour of sealing wax, which is used less but more harmoniously. This works show a composition entirety, which is almost absolute, with contributions certainly from the whiteness of round, concave, or convex shapes, and full volumes that cannot be geometrically identified, but resulting from occasional swellings, in a surface tension of aerial levity. Great significance is given to the use of sealing wax, as opposed to white swollen shapes, sometimes used to articulate the volumes with the counterpoint of small devices, possibly screws, pins, bolts, which are rigorously aligned. Sealing wax determines a violation of austere, essential structures, when it covers irregularly silver laminas with minimal burrs, as if it had just been melted, ready to be stamped with a seal, a heraldic figuration. Graziella Folchini Grassetto, director Studio Gr.20 in Padua, IT Photography: Gerhard Jaeger |